Aluksi kirjoitus myöntää, että Lännen ylivalta on ollut suhteellisen hyvää aikaa. Kuten professori Ian Morris kirjassaan War! What is it Good For? for osoittaa, maailma jota yksi suhteellisen sävyisä suurvalta dominoi - vastakohtana ns. monikeskisyys - on käytännössä paras mahdollinen. Rooma, Britannia ja USA ovat vuorotellen dominanssillaan lueneet suhteellisen hyvän maailman, missä kauppa kukoisti, elintaso nousi ja väkivaltaisten kuolemien määrä laski. Pax Romana ja Pax Britannica toimivat pitkään, mutta syistä jota käsittelin aiemmin, ne eivät olleet sustainable (kestävä) vaan hiljalleen kuihtuivat. (Katso liite tämän postauksen lopussa.) Morris pohtii vuonna 2013 ilmestyneessä kirjassaan myös sitä, miten kauan USA:n mahtisema säilyy.

The retreat of the West is not universally welcomed. There is still no substitute for Western leadership, especially American leadership. Sudden withdrawals of American support from Middle Eastern or Pacific allies, albeit unlikely, could trigger massive changes that no one would relish. Western retreat could be as damaging as Western domination.

By any historical standard, the recent epoch of Western domination, especially under American leadership, has been remarkably benign. One dreads to think what the world would have looked like if either Nazi Germany or Stalinist Russia had triumphed in what have been called the "Western civil wars" of the twentieth century. Paradoxically, the benign nature of Western domination may be the source of many problems.

THE WEST'S OWN UNDOING

Huntington fails to ask one obvious question: If other civilizations have been around for centuries, why are they posing a challenge only now? A sincere attempt to answer this question reveals a fatal flaw that has recently developed in the Western mind: an inability to conceive that the West may have developed structural weaknesses in its core value systems and institutions. This flaw explains, in part, the recent rush to embrace the assumption that history has ended with the triumph of the Western ideal: individual freedom and democracy would always guarantee that Western civilization would stay ahead of the pack.

Only hubris can explain why so many Western societies are trying to defy the economic laws of gravity. Budgetary discipline is disappearing. Expensive social programs and pork-barrel projects multiply with little heed to costs. The West's low savings and investment rates lead to declining competitiveness vis-à-vis East Asia. The work ethic is eroding, while politicians delude workers into believing that they can retain high wages despite becoming internationally uncompetitive. Leadership is lacking. Any politician who states hard truths is immediately voted out. Americans freely admit that many of their economic problems arise from the inherent gridlock of American democracy. While the rest of the world is puzzled by these fiscal follies, American politicians and journalists travel around the world preaching the virtues of democracy. It makes for a curious sight.

The same hero-worship is given to the idea of individual freedom. Much good has come from this idea. Slavery ended. Universal franchise followed. But freedom does not only solve problems; it can also cause them. The United States has undertaken a massive social experiment, tearing down social institution after social institution that restrained the individual. The results have been disastrous. Since 1960 the U.S. population has increased 41 percent while violent crime has risen by 560 percent, single-mother births by 419 percent, divorce rates by 300 percent and the percentage of children living in single-parent homes by 300 percent. This is massive social decay. Many a society shudders at the prospects of this happening on its shores. But instead of traveling overseas with humility, Americans confidently preach the virtues of unfettered individual freedom, blithely ignoring the visible social consequences.

The West is still the repository of the greatest assets and achievements of human civilization. Many Western values explain the spectacular advance of mankind: the belief in scientific inquiry, the search for rational solutions and the willingness to challenge assumptions. But a belief that a society is practicing these values can lead to a unique blindness: the inability to realize that some of the values that come with this package may be harmful. Western values do not form a seamless web. Some are good. Some are bad. But one has to stand outside the West to see this clearly, and to see how the West is bringing about its relative decline by its own hand. Huntington, too, is blind to this.

LIITE Aiempi tekstini siitä miksi Britannian mahtiasema loppui 1800-luvun loppua kohti

Stanfordin yliopiston klassisen historian professorin Ian Morrisin kirja War! What is it Good For? Conflict and the Progress of Civilization from Primates to Robots käsittelee sotaa esihistoriallisesta ajasta pitkälle tulevaisuuteen. Kirjan aihe on tarkemmin ottaen sodan vaikutus ihmisen instituutioiden kehitykseen. Referoin kirjaa tässä kuitenkin vain siltä osin mikä on relevanttia tämän artikkelin aiheen osalta.

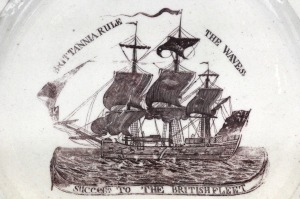

1800-luvun suhteellinen rauhantila maailmassa johtui pitkälti yhden valtion – Iso Britannian – mahtiasemasta maailmassa. Pax Britannica ei Pax Romanan tapaan koskenut vain Britannian vallan alla suoraan olevia valtioita, vaan maailman meriä.

1700-luvulle tultaessa Britannia alkoi muuttua perinteisestä siirtomaavaltiosta yhä enemmän kauppavaltioksi. Pohjois-Amerikan varakkaat siirtokunnat itsenäistyivät, mutta Britannian kauppa kukoisti. Kauppa edellytti brittiläisten laivojen turvallista liikkumista maailman merillä. Sitä varten Britannia loi vahvan laivaston ja monopolisoi väkivallan merillä itselleen niin kuin nykyaikaisen valtion poliisitoimi monopolisoi väkivallan maan alueella.

Britannia ei kuitenkaan monopolisoinut merenkulkua brittiläisille laivoille, vaan loi maailman meristä yhteisresurssin, jonka turvallisuudesta Britannia pyrki huolehtimaan väkivaltamonopolinsa avulla. Britannia hyötyi – sen bruttokansantuote oli neljännes koko maailman bruttokansantuotteesta – mutta niin hyötyivät monet muutkin maat.

Britannia ei kuitenkaan monopolisoinut merenkulkua brittiläisille laivoille, vaan loi maailman meristä yhteisresurssin, jonka turvallisuudesta Britannia pyrki huolehtimaan väkivaltamonopolinsa avulla. Britannia hyötyi – sen bruttokansantuote oli neljännes koko maailman bruttokansantuotteesta – mutta niin hyötyivät monet muutkin maat.

Britannia teki väkivaltamonopolinsa turvaamiseksi tylyjäkin tomia – esimerkkinä buurisota. Se ei sinällään ollut muuttunut sen vähemmän itsekkääksi kuin aikaisemmin, mutta Britannian toimet oman edun ajamiseksi johtivat positiivisiin ulkoisvaikutuksiin muille valtioille.

Ongelma väkivaltamonopolissa ei niinkään ollut se, että Britannia oli maailmanpoliisi, jota muiden piti totella. (Britannia mm. kielsi yksipuolisesti orjien kuljetuksen maailman merillä ja pakotti muiden maiden laivat noudattamaan päätöstään.) Ongelma oli pikemminkin se, että tasapainotila ei ollut kestävä.

Vaikka väkivaltamonopolin turvaama maailmankauppa toi rikkauksia briteille, se toi rikkauksia myös muille maille. Britannian osuus maailman bruttokansantuotteesta laski 23%:sta 14%:iin. Muutkin maat rikastuivat ja keräämillään varoilla USA, Japani ja Saksa alkoivat varustaa armeijaa ja sotalaivastoa.

Väkivaltamonopoli mureni hiljalleen. Britannia joutui ensin antamaan läntisen Atlantin väkivaltamonopolin USA:lle, sittemmin väkivaltamonopoli mureni laajemminkin. Vanha tasapainotila järkkyi.

Rauhantila päättyi vuonna 1914. Ensimmäinen maailmansota ei myöskään osoittautunut yksittäistapaukseksi vaan ensimmäistä maailmansotaa seurasi toinen.

Japani osoitti kouriintuntuvasti, että fyysisen voiman käytöllä voi edelleenkin saada suuria etuja. Kun länsimaat kärvistelivät 30-luvun lamassa, Japanin talous nousi kohisten mm. Mantsurian anastuksen takia.

Ei kommentteja:

Lähetä kommentti